-

Voodoo Tactical

Voodoo Tactical 20-972 Embroidered Blood Type Tag with Velcro

Original price $4.95Sale price $3.81 -

Safariland

Safariland Model 777 Slimline Triple Magazine Pouch for Glock 20 21

Original price $53.00 - $72.50Sale price $42.40 - $58.00 -

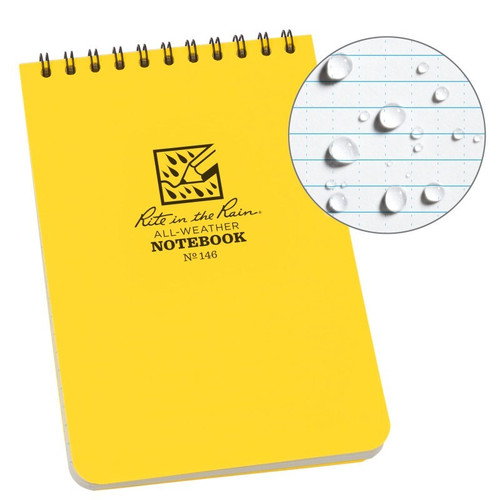

Rite in the Rain

Rite in the Rain All-Weather Top Spiral Notebook (4'' x 6'')

Original price $5.95Sale price $5.63 -

Voodoo Tactical

Voodoo Tactical 15-0058 Custom Series Mini Tobago Pack

Original price $109.95 - $119.95Sale price $93.95 - $99.95 -

BLACKHAWK!

Blackhawk S.T.R.I.K.E.® Small Radio/GPS Pouch - MOLLE

Original price $29.95Sale price $22.27 -

-

BLACKHAWK!

Blackhawk 37FS49BK Foundation Series Flashbang Pouch, Black

Original price $24.95Sale price $18.58 -

GH Armor

GH Armor HB2 ACH Level IIIA Ballistic Helmet

Original price $919.00 - $979.00Sale price $540.34 - $586.20Free Shipping -

Battle Steel

Battle Steel BS625-2036III+WS TACLite Ballistic Shield with View Port Level III+ M855/M80 7.62mm, 20" x 36"

$1,966.13Free Shipping -

Boston Leather

Boston Leather Model 5574 Strion Loop Holder

Original price $18.60 - $22.20Sale price $12.05 - $14.37 -

Safariland

Safariland Model 777 Slimline Triple Magazine Pouch for STI 2011

Original price $57.50 - $72.50Sale price $46.00 - $58.00 -

Safariland

Safariland Model 777 Slimline Triple Magazine Pouch for Smith & Wesson M&P 45C

Original price $57.50 - $72.50Sale price $46.00 - $58.00

Tactical & Duty Gear

Explore our range of tactical and military gear, tailored to meet your operational needs. From deployment gear to military police equipment, we've got you covered. We prioritize reliability, offering gear from top manufacturers like BLACKHAWK!, Bianchi, Safariland, and Streamlight. Whether you're outfitting an agency or unit, streamline your procurement process by sourcing all your gear from one place. We provide worldwide shipping to military APO/FPO addresses via USPS priority mail.

For law enforcement officers, duty brings a spectrum of situations, from assisting lost tourists to confronting violent criminals. Our modern duty gear ensures convenient portability for essential equipment, such as handcuffs, radios, flashlights, and spare magazines, with a complete loadout weighing around 20 pounds. Designed for waist-level accessibility on a standard duty belt, our gear enables officers to swiftly access and deploy equipment in emergency situations.

Free Shipping On

Orders Over $99

Return Within

30 Days

Most Orders Ship

Within 24 Hrs

Secure Online

Shopping